The Bubble of a Dream

Selected for The Year’s Best Sports Writing 2021 collection

A dream doesn’t make a sound when it dies. With no reason to exclaim, the aspiration simply slips away with a sickening silence.

January 19th, 2020

Exhausted and stunned, I stumble forward reluctantly.

Dehydrated and sore from having just battled 26.2 miles of windswept streets, I pause in panic, fearful of moving forward because once I leave this chute it’s over. Accepting a finisher’s medal will mean this dream is done.

Salt covered and in a daze, I stare out in search of support, but all I find are the faces of fans pressed up against the fence of the 2020 Houston Marathon straining to find their loved ones. They have no idea how much my world has just altered.

Having failed to qualify for the USA Olympic Marathon Trials by a handful of seconds, for the third time, I fight back tears with slow breaths that decompress me into the air outside the bubble of purpose and passion I’ve lived within the past two years.

Two years earlier…

My mind raced to make sense of how life had just changed while my tired body rested in the seat of a plane rising gently up over a setting Northern California sun.

To this day I was a steadily improving amateur marathoner moving up year-by-year amid the masses. I’d sought and gained meaning from breaking one threshold after another. An enjoyable hobby that had brought me from Boston to Chicago to New York. But I’d begun to fear that my ascent was approaching its peak.

I’d broken 3, then 2:50, 2:40, and even 2:30. But as my ability increased I began to question the value of shaving another few seconds off my personal best. I’d enjoyed moving up the ranks of nonprofessionals, but questioned the value in dedicating so much time to a hobby.

Running 2:29 felt like an arrival; a distinction understood by fellow runners. A subsequent 2:28 was a feather in my cap, but did this mean I’d reached the end of the road? Since what difference would running 2:27 make? How much could a 2:26 or even 2:25 alter my reality? I’d wondered.

But we had just run 2:23.

My teammates and I had tossed caution to the wind that morning in Sacramento — and it’d worked.

“BROMKA WHAT ARE YOU DOING?!” A friend had shrieked in alarm at halfway. But we’d finished what we started, only slowing slightly by the end. This leap forward moved my teammates and me from the no man’s land of amateur marathoning onto the brink of sub-elite distinction: The 2020 USA Olympic Marathon Trials.

“Are you gonna try for it?” my wife Julia questioned before I’d even had time to conceive of what “it” would demand. The prospect of earning entry to the dream competition two years away made my mind race and stomach churn. Running the required time of 2:19:00 felt nearly unfathomable.

Almost. But that glimmer of a chance held my eye.

Earning the opportunity to run in a race where the top-3 qualify for the Tokyo Olympics felt like a goal worthy of engrossing my heart and sapping my body. The problem was I had no idea what it would take to even have a chance to try. Sure, in theory, it would simply be more of the same. More training, more focus, more intent. But that sounded too simple.

Failure was probable.

Injury was likely.

The only guarantee was weariness. The act of even trying consistently for something this difficult for that long would demand more, for longer, than I’ve ever attempted.

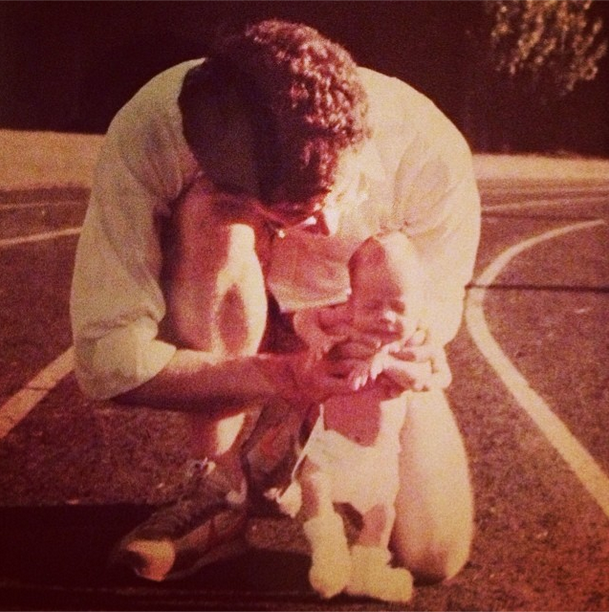

Raised a runner, I’ve known the sport since my earliest memory. My father brought me along to road races as an infant and mentioned history’s greatest athletes as typical dinner time conversation. As a teen, I wanted to be fast, just like all children exploring their newfound strength, but I was mostly marginal.

By college, I was all consumed. Each day was spent in the spellbound state of a student-athlete: the imbalanced excitement of amateurism. Trying to cram more of everything you love than can fit into each day. Foolishly believing that if you just “want it” more you’ll be better. Sadly, that mostly led to injury and heartbreak. Led to forcing in a sport that demands patience.

Such is youth.

All of that felt like a lifetime ago because it was. Over a decade gone by, a career, a wife, and now a son added to life’s juggle, I was concerned about becoming all consumed by an outlandish ambition.

Dreaming this grandly felt almost childish. But reimagining myself this late in my athletic life was mesmerizing. Improving these past years was one thing, but qualifying among the nation’s best, while approaching forty, offered a chance for a crisp title of distinction: “Olympic Trials Qualifier.” That’s the type of thing you could be remembered by forever. But what would such a dream even demand?

I poured everything I understood of the endeavor into an essay titled, “Burn the Boat,” an homage to an idea I’d read about that the only way to achieve something heroic is to eliminate all other options. Part road map ahead, part love letter to the sport, part ode to the doubters — I explained to the world, as well as myself, the ridiculousness of the dream in detail. Cutting another 11 seconds per mile from my pace was unlikely at best, harmful at worst. I needed to own the improbability of success to prevent others’ doubts from dissuading me once I begin.

With my intent posted for the world, and before I understood the significance of our commitment, my teammates and I were forging a path toward an attempt to qualify a year later at the 2018 California International Marathon.

Stepping into this dream out of curiosity, over the following two years it would impact nearly each of my days, affect almost all my relationships, and leave an indelible impression on my identity.

Spring 2018

Anxious, I began the final training run of my week at a shuffle. By the time I beeped my watch to finish, I’d stare at the 12-miler with pride for what it completed: my first 100-mile week.

And I wasn’t broken!

Of course, the body doesn’t understand exact mileage. An injury can occur anytime, not simply while passing an arbitrary empirical threshold. Having run for over twenty years, I’d never accumulated triple-digits in a week.

But I’d need to.

Though our qualifying attempt was still eight months away, I was already in debt. My fastest teammates had either enormous talent or years of accumulated mileage. I had only modest amounts of either. Unable to rewrite my genetics, I needed to increase my training load as fast as possible without injury. It’s the easiest mantra for a runner to say, such an elusive line to actually walk.

The essence of this dream was calculated risk.

A late Sunday in April, walking out of historic Hayward Field having just finished in 3rd place in the Eugene half-marathon, I was filled with subdued satisfaction. It was a good day, the plan was working, but we would need more.

The lesson I was learning was simple: running more makes running easier. That morning I’d felt more comfortable at a faster pace than ever before. An ego boost, but only a small step towards the goal.

A 2:19 Trials Qualifying marathon is two 69:30 half-marathons back-to-back. Ideally, you’d be able to pass through the first one well within yourself. At ease and breathing calmly. Having just run barely a minute better than that pace, 68:23, I was proud, but it only granted me marginal self-belief.

Pulling my phone from my bag revealed a text from my dad, “Today was a great start toward December. Now just believe and do the work and savor every time you run.” A compliment wrapped in context. The day mattered mostly as momentum for the future.

Our endeavor in the fall was far from certain. We had half a year to get comfortable at 5:18 per mile pace. Though it might be possible, it was unlikely to ever be comfortable.

We had work to do.

Fall 2018

“Marathon training is kind of a trust fall,” Patrick philosophized.

A methodical man of understated Southern manners, Patrick doesn’t overstate or theorize indulgently like I do.

My closest training partner, I wouldn’t be where I was without him. When we met years ago I was a marathoner, but I wasn’t pushing hard. Participating, but not truly testing. I’d do easy long runs and a workout here or there. That isn’t Patrick.

The man is a metronome.

He ran fairly well as an amateur in 2010.

Then slightly better in 2011.

And even better in 2012.

His progress continued each subsequent year.

Averaging over 4,000 miles annually for the past decade, he gets in a 10–11 mile run each day. Everyday. Regardless of life’s bumps or curves.

I took his metaphor for our training as an omen, even he understood that this attempt for the Trials would be a leap. He’d been dusting me in workouts, but calculations for race day left him uncertain. We’d repeatedly turned up the dials on our training, but lacked the data to know how all of this effort and fatigue would translate into the final miles of a marathon.

Ten miles at qualifying pace after a ten-mile warmup gave us confidence, but how much?

Twenty miles at our previous race pace completed while chatting, felt great, but what did it mean?

I knew that no one workout signals the sum of a training block, but if I couldn’t breathe calmly at qualifying pace it would be impossible to enter the race with belief. It’s easy to explain failure in hindsight, to reason it away in the aftermath. What’s difficult is anticipating being broken by a dream and still continuing on.

One Month till CIM 2018

The pressure of this endeavor was threatening to break me before the race even began.

“What if I fail?” I wondered.

As other marathons took place across the country and dozens of talented runners I knew failed to qualify it framed the difficulty of this dream. If these men, athletes who’ve beaten me on every occasion, couldn’t even crack 2:20, what hope did I have to even finish the race at such an absurd pace?

Was I wasting my time reaching for this idolized echelon?

I didn’t know. But I did feel strong.

I was able to shift gears with abandon and stretch out my stride further than ever before. This fitness felt incredible, but if I couldn’t run below 2:19, was it all meaningless?

Such thoughts were compounding the existing fatigue from months of high mileage, sending me towards sadness.

Maybe I should simply play it safe, I considered.

Surely I could shatter my personal best. I could surge into the finish with satisfaction. The guys attempting to qualify would be off in the distance, but that would be okay, right?

Sadly not.

“That’s not what got you here,” I remembered. I’d announced my goal to everyone I knew because if the dream was beyond me, maybe I could cross over to it on a bridge of belief built on the hopes and dreams of others. This attempt felt wholly outside of my experience. But that was the point.

I must endeavor to qualify because of what the threshold signifies — that I was among a group who are able. If I aspired to be with them I could not hide in the safe harbor of myself.

Like when you step right up to the edge of a cliff above the ocean and force yourself to peer down, I had to own the intent of this endeavor or it would end in regret.

Resigned to fear, which seemed certain, I swore off caution, which I could not afford.

The 1st attempt — The California International Marathon

Stepping to the line I was filled with a good fear. Though not quite at Patrick’s fitness level I would follow him until I faltered. There were simply too many unknowns to go on this journey alone.

As the sun began to rise, a year removed from the race that changed how we thought of ourselves as runners, we were about to step up and hurl a half-court shot, together. If last year we reached the logical limit of ourselves as aging amateurs, this past year had been an exploration of how far we could make it if we truly dared to dream.

We were about to find out.

“Crack!” the starter pistol fired, and we were off in a stampede. Having raced a dozen marathons previously, the intensity of this attempt was unlike anything I’d ever experienced. A pack of so many men extended right to the edge of their ability, aligned in the same pursuit. Many of us would fail, that truth was understood. The point was we were there to try.

5:16

5:17

5:07

5:14

5:14

5:12

5:18

5:15

Splits are flying by faster than I’d ever experienced before. Having raced this course twice, I was experiencing it in an entirely new way. Like playing your favorite record at double speed, each rise and roll sent my breath gasping.

“We’re doing this!” I celebrated internally, even as I understood that the true measure of a marathon wouldn't begin for an hour. Sure you can tuck away seconds under pace early on, but it’s crushingly easy to hand back minutes in the end.

Rising up a slight incline into a slanting sun, my heart rate began to feel like an engine revving off its block. “Too hot” I cautioned. Panicked, I attempted to understand why the pack around me was surging now.

“Our splits are fine, no need to accelerate!” I whined inside, but this horde of humanity wasn’t dictated by my desires.

5:11 — a totally respectable mile, only to get dropped by the pack.

I was pissed.

Alone.

And over an hour from the finish.

“Shit. Shit.” my wife muttered as Patrick traveled past her without a sign of me alongside.

Here I came up the road ten seconds later. How do you encourage an athlete as he begins to slip?

“YOU GOT IT! COME ON PETER YOU GOT IT BABE!” She screamed, I could tell she was hollering hoping to make it true. I couldn’t spare the energy to acknowledge her encouragement, but I was still traveling at a rapid rate.

The final nine miles of a marathon are chapters of descending discomfort. The obstacles to running fast begin to compound as the body’s temperature rises, the muscles dehydrate, and sugar levels fall off a cliff.

Not a single step of these miles would be easy, but I still had a chance.

5:20

“Shit, there it is, over pace.” It’s the split I’d been dreading for a year. What will I do once I’m finally confronted with the threshold of failure? I’d wondered for 52 weeks.

The only thing there was to do: anchor and re-anchor my mind forward a block at a time to compel my body to continue.

This is where marathoners give up. Where defeat is so understandable it’s almost assumed. In the final few miles, a marathoner’s stride becomes taut. While before their body bounced and hung in the air, it now hits and jolts against the ground. My heart rate peaked as my stride began to shorten.

With close to a thousand steps per mile, the sensation of slowing from the qualifying pace of 5:18 per mile to a pace that is too slow, 5:25 per mile, was nearly imperceptible. The difference was only inches. It’s each stride lasting simply a moment less. The cruelty of distance running: the difference was slight, but the distinction was significant.

Seeking to distract my mind from such mathematics, I focused on the truth that a friend had imparted:

“Run fast because you can,” she’d urged.

At the final stage of a race, there is no strategy. There is only effort. What’s required is the audacity to check and recheck the empty bank account of your ability, to scour for any final deposits until the finish.

Nearing the final bend I understood that I was slowing. The past year of effort might not get me to the Trials this day, but I was sprinting down the streets of Sacramento faster and with more inspiration than ever before.

There’s a cruel finality to a marathon run right at your edge, that after over two hours of running your mind can barely accept the challenge of the final few minutes.

It simply feels too difficult to grasp.

All the while your legs continue to churn, repeating on the flywheel you started before sunrise.

Turning the final bend to the finish my knees drove and back arched to reveal the clock having just rolled past 2:19. The qualifier was gone, but I was about to break 2:20. A time that only shortly ago would have felt unimaginable.

Embracing Patrick, he’d done it. He was a 2:17 marathoner and a qualifier for the 2020 Olympic Trials a year later in Atlanta.

Embracing Julia we simply sobbed. From sadness, from happiness, from pride, a bittersweet cocktail of them all intertwined. Arms wrapped around her, head hung forward, my tears dropped straight to the cement. Too exhausted, invigorated and inspired inside to worry about how I looked on the outside.

This dream brought me further this day than ever before. This dream took more from me the past year than I’d previously known I could give. Though not yet at their external standard, I was now a runner fully reinvented from my former self.

After taking moments to breathe I checked my phone. Scrolling across hundreds of texts, from congratulations to condolence, I stopped on one from a runner friend, “I’m missing out! Let’s go get that 2:18:59 together!!”

A smile creased across my face as I realized the truth that had become obvious to everyone: this dream was just beginning…

Spring 2019

Approaching the 123rd Boston Marathon I felt unexpectedly light and excited. While ordinarily racing in Boston demands pressure and sacrifice, this time I was doing so with my focus set elsewhere, on another attempt at the Trials qualifier that coming December. So now I was somehow able to run America’s oldest marathon without the usual burden of expectation.

Like an orbital slingshot, when they direct a rocket around a planet in order for it to pick up speed, I was aiming at this Boston excited to race, but mostly focused on using it to gain fitness en route to another flat course attempt in Sacramento.

“Heck of a workout this morning! Take confidence from this!” a friend texted after a morning in which I’d run four times four miles at close to my half marathon best pace. We were two months out from Boston and the splits I was running barely made sense, but they were not what I was focused on. I was simply attempting to keep up with my teammates. They were pulling me to personal best efforts weekly while I was just hoping to contribute to our collective goal of winning the 2019 team title in Boston.

The team competition is scored by the lowest total time from a team’s top three finishers. As a group of amateurs, we’d supported each other in this exhausting hobby for years on end and figured we might as well try and earn a trophy together in the process.

By the time it was over I ended up finishing 1st for the team, 33rd in the race, and we won the team title together. Improving my Boston best by over five minutes somehow felt like a side-show, a bonus, a supplement to the main affair.

I had seven months to prepare for my final attempt at the OTQ.

Summer 2019

“It takes an amazing amount of confidence in your condition, and belief in yourself, to rest.”

Ryan Hall, America’s fastest marathoner, said this in the latter half of his career after he’d broken himself repeatedly. His wisdom was gained through years spent not exhibiting such self-confidence.

For the half-year preceding my second attempt I aimed to emulate his intent, not his actions. I was in a circling pattern, an arc of training intended to ascend without overextending. A balance of strain and ease. It was a tricky tiptoe to walk when your mind simply wants to dive in.

Though my body was in a holding pattern, my identity continued to be absorbed by the pursuit of the dream.

“How’s training?!” was friends’ most common question. They understood that each of my days was marked in relation to a future date. And I began to notice that the goal served as both a sword and a shield in my daily life. It offered excitement to attack each day and braced my ego when I felt vulnerable.

Early one summer morning as I walked off the sky bridge onto a 737 aircraft to fly in coach across the country I was confronted with self-doubt as I encountered the 1st Class cabin.

Though subtle, I sensed their superiority.

Though unstated, I assumed their success.

If they have all of this, the wealth required to fly in such luxury, what do I have? I wondered.

My OTQ chase.

The pursuit of this goal, with its resulting strength and focus, had come to define my self-worth. I was proud of my pursuit. My identity consumed not just by being a runner, but by being someone committed to finding more speed each day.

Maybe he’s an executive? I’m a marathoner.

Maybe he drives a Tesla? I’ve run 2:19.

Though I understood such judgment was petty and insignificant, I couldn’t stop myself. I was consumed by a dream that I stumbled upon at a moment I’d been seeking meaning.

As a working professional, running was not my job. The main hours of my days were dedicated to earning a living, providing for a family. But after a decade as a business consultant, I’d begun to question the true meaning of my work. White-collar, professional service is a prudent pursuit that often lacks emotion and consequence.

As an amateur marathoner, I’d stumbled upon depths of personal meaning, vivid physical experience, and a rich international community, which had eluded me in the professional world. Sure, this pursuit was all for fun. But, decades removed from my earliest athletic endeavors, I’d begun to question if these games we play are in fact the essence of who we are.

With less than a year to go before the Trials, I wasn’t the only amateur athlete attuned to this dream. A swelling crowd of men and women across the country had declared their intent to chase the OTQ. Already the largest field of qualifiers ever, the 2020 Olympic Marathon Trials was shaping up to be momentous. Though only the top-3 from each race earn Olympic entry, hundreds now saw the pursuit of qualifying as a life-affirming pursuit. But for me, it already felt like an old foe.

I would begin this fall as a dad approaching middle age who was faster and better prepared than ever before. If this was a form of mid-life crisis, it felt incredible.

The only thing to do then was begin.

Fall 2019

The 12 weeks between Labor Day and December’s California International Marathon frame the fall as if the season was designed for runners to excel. If last year’s attempt was a half-court shot that could have banked in on a fluke, this year’s race was a 3-pointer. Like I was coming off a screen and sliding deliberately to a trusted spot behind the arc, I was waiting to receive an outlet pass that I knew I could hit, but was far from certain.

35 days before CIM

101 miles in 6 days. Two workouts faster than ever before.

Still, I was sad.

It was probably just fatigue. I was depressing my body with daily training. And by caring so much about something I couldn’t control. It hadn’t gotten any easier over the past year. If anything it was getting worse as the deadline approached.

21 days before CIM

“What does that mean?” I wondered. We’d just ran 16 miles at qualifying pace and it hardly felt hard.

“I wish we could just do it right here, on our practice route,” I told a teammate. But of course, that’s not how the marathon works. Race day involves so many more variables than a practice run.

I attempted to appreciate the simple beauty of being this able. The journey of forming my body into something that can sustain at a previously unimaginable pace. The plan was working.

But it’s those final miles that make the Marathon.

One day till CIM

“I’ll go 14–16, then roll-off,” Patrick confirmed. He was there to pace several of us, and though his presence would be a comfort, he’d be gone by the time the real work started.

My father was there as well.

The pieces and people were in place for a great day. It was time to execute.

“You’ll need to finish it,” I repeated to myself softly. There’s a chasm between ability and belief, a divide that’s not always clear how to cross. Sometimes it’s something you step over without hardly noticing, “Oh look, I did that!” you delight in hindsight. Other times the span to overcome feels never-ending as if tiptoeing out into space blindfolded, continuing on faith alone.

At 38 years old I felt stronger than ever before, but reaching the finish line under 2:19 would take an extra leap.

The 2nd attempt — The California International Marathon 2019

The starter pistol cracked and we were off.

The most startling sensation was the size of the pack surrounding us. My teammates and I were engulfed in a mass of humanity — over a hundred men were rising and rolling the California hills in unison. A mass of Trials hopefuls much larger than previous years. Some settled, many stressed, it was early still and the breathing around me was already audible. I admired these men for dreaming, for arriving on the day prepared to try, but we had too far to go to be straining just yet.

“Climb the ladder.” I reminded myself. Fearing I might obsess about the final miles and make a mistake before I arrived there, I settled on this mantra to keep my mind on the moment at hand. After all, you can’t climb to the top of a ladder without stepping up the bottom rungs first. My mind screamed for the chance to take on the final miles where I had failed last year, but it’d have to wait for now.

Halfway — we were 23 seconds under qualifying pace.

The middle miles can gnaw at your psyche, twisting you into unusual versions of yourself.

“Let’s do this motherfucker!” I snarled to a guy next to me after Patrick had rolled off. My mind was cycling through a carousel of emotions: excitement, fear, sadness, and anger. But no amount of trash-talking the marathon will have any effect. You simply do what you can to get yourself through.

Approaching the final 10k, moving faster, and feeling better than ever before, my mind was consumed by its arrival into the moment that it had fixated upon for months.

But my body was beginning to ache.

Muscle soreness is expected, what concerned me was the feeling I was being baked inside. It was the humidity, uncharacteristic for this wine region, that was softening my resolve. Not a sharp pain, but a woozy sensation of intoxicating systemic fatigue.

Expecting to suffer, I’d buttressed my mind in preparation. Two years in the making, I’d finally arrived at the moment I’d written about so long ago.

The moment I’d warned myself and others might be too much.

I had the chance that others envied.

“They all wish they were here.” I reminded myself.

“We’re all rooting for you. You’re a mini-celebrity over here.” A friend had messaged me from New York the week before. I’d been overcome with emotion. These men, many I don’t even know, cared about my success.

Why?

Maybe they’ve read my writing? Maybe they’ve followed my progress? Why were they so invested in my success?

I was one of the few left from my generation still fighting for more speed. Still believing their fastest days are ahead. If I could, maybe they could have, or even still can. Their care for me means I could not indulge in self-sorrow. This moment was my opportunity.

But all the well wishes in the world wouldn’t close these final miles for me.

The final 5k I was surging, passing people, but something didn’t feel quite right. Glancing at my watch, the status was grim. Like attempting to reconcile a stack of bills with a budget that just won’t balance, I was slipping back seconds to the standard with too few to spare.

“WAKE UP! You need to fucking face it!” I implored myself. I felt better than ever before, but my past wasn’t the measure of the Olympic Trials standard. The time wouldn’t be moved by my effort. I was fighting through the fatigue by delusionally believing that I was still on track.

“You’ve run so many good splits. You’re gonna do it!” I encouraged myself. If only positivity made it true.

And then I heard it, “YOU’VE GOTTA GO!” My teammates, standing at the marker for a quarter-mile remaining, screamed with utter urgency. Finally, the truth.

My knee popped up…my hand raised high, and I simply began to sprint.

At their essence, moments like these are all the same, the sensation identical to high school two decades ago when I dashed for the schoolyard finish line.

Rounding the final turn toward the California State House my head tilted up to the nauseating reality that I had only a dozen or so seconds to make it over a hundred meters.

Every step was a full body squat. Every arm swing ached like a bicep curl.

I might fall.

I may fail.

I just had to make it to the line.

Dad

Minutes passed without a word.

There’s nothing he needed to say, and I couldn’t summon a sentence. We’d been there before. My most memorable sports heartbreaks flashed through my mind.

The Cross Country races in college where I’d underperformed.

The District track meet in high school where I didn’t hit the time.

Even my nearly undefeated elementary school soccer season that ended in defeat.

We’d experienced the heartbreak of sports together before, but it’d been a long time.

That’s maybe what was most remarkable, how little the simple feeling of competitive disappointment had changed as I aged. Though a son approaching forty hardly needed his father for emotional support on Race Day, this day was different.

Because this goal was different. It had opened me up so widely, demanded so much intent and aspiration, that it stripped away the layers of emotional protection and perspective a grown man carries around with him each day.

All of a sudden I was back on that soccer field, standing in the cold November drizzle, sobbing as I struggle to make sense of the last-minute loss. I could still see the fir trees that lined that field as I recalled that first athletic heartbreak. To want something so much and realize it’s not possible.

A father and son may be able to reminisce generally about the younger’s successes and victories, but they can recall every detail and element of the losses and failures. In high school, it was .24 seconds that kept me from the State Meet. I cried about that split second for weeks and let it define me for a year.

This day it’s two.

2:19:02

Angrily hurling my soggy singlet against a fence did nothing. A scream had no effect. Before I knew it I was back on the ground with my eyes closed, unable to take in any more of the moment.

The best race of my life. The fastest I’d ever run, the best I’d ever felt, was a failure?

Last year’s 2:19:40 was clear: I tried and wasn’t able. Capable but not that close.

Ironically, in some ways, I felt unburdened. Having carried the weight of insecurity about whether I’d be capable for over a year, I nearly had. Such a close miss meant that all that work, all that worry, every ounce of effort, had added up to something worthwhile. It meant that the plan I obsessed over and enacted for two years was in fact correct.

“I am capable of being a Qualifier!” I celebrated to myself between the tears.

And yet I wasn’t.

I hadn’t gotten it done.

Like the man who won the lottery but lost the ticket, I was successful, yet no different than before. Just as irrelevant to the OTQ.

Having my father there was welcome but unnecessary. After this many years, his care was understood, his guidance engrained. Quite simply, this entire chapter of my athletic life is a gift, because it was something he nearly missed.

Nearly a decade ago, when his heart stopped, I was no longer competing. I’d figured my days of endeavoring athletically were behind me. But as his arteries began to heal I had re-entered the competitive running scene, for no real reason except I had realized how soon the option to pursue speed would pass me by.

The gift he gave me as a kid had kept us close these past years. A father and son can’t call each other constantly simply because there will be a day when they are unable, but they can use sport as an excuse to connect. Texting to celebrate a successful workout, discussing the final details before an attempt, or taking time together to consider what’s next.

I will never know how much I’d care about running if he hadn’t given it to me at birth.

The simplest sport used to build the most foundational relationship.

A day later

“You’ll know.” My dad advised, softly.

Seconds passed with nothing to say. I may forever regret how the day before finished, but time was already moving forward.

My pride in how my teammates and I typically execute on race day threatened to swell into hubris. The question at hand was whether I should head to Houston for a final, unplanned attempt at the qualifier in just 41 days. The USA Olympic Marathon Trials qualifying window would close on January 19th.

I was incredulous.

This wasn’t what I'd prepared for. I’d seen too many talented runners chase standards with decreasing returns to get caught up in such behavior. That was never supposed to be me. We prepare with intention and execute with composure. We don’t hurry. We don’t do vanity races or ego intervals. We pick our shot and hit it.

Except I hadn’t.

So now I was forced to scramble. To seek advice for the future even as I was still processing the past.

Two days after

“You failed. Sorry man, but that’s the truth. You were over.” A friend reflected on the harsh reality.

It hurt to hear but helped to process without sugarcoat or caveat.

“Yeah, man. It’s true. Thank you.” I replied with the lump from Sunday still stuck in my throat.

“I mean, I appreciate the support from everyone for sure. But you’re either in or out.”

I hadn’t qualified. I wasn’t a qualifier.

The overwhelming impulse is to support those who struggle. But the goal was to qualify, and any number of seconds over was too many. It hurt, but the truth was refreshing to face with a friend.

Two days removed from missing the standard for the second time I was reeling and tumbling like a tissue in the wind. Updrafts of excitement for racing at such a pace, followed by the sharp sinking realization that in terms of The Trials it meant nothing. Twenty-six and two-tenths miles completed, I’d fallen less than ten feet short.

“You really thinking of trying again?!” He questioned skeptically.

“Considering it for sure,” I replied hesitantly, hoping that saying it aloud would convince me.

Feeling so many things at once, the most consuming sensation was numbness. And the messages kept pouring in…

“We’ve never met but I just had to say…”

“We don’t know each other but I wanted you to know…”

“I admire…”

“You inspire…”

A lifetime’s worth of care and consolation. More love than any one runner deserves.

But I hadn’t intended for any of this!

Qualifying was supposed to prove that wild dreams were worth chasing. That limits are simply cages we create for ourselves.

But no. I’d fucked it up. Entering the final mile I had 5 minutes and 28 seconds left to qualify. But I’d taken 5:30.

Frustrated at myself for failing, I continued to swipe open my phone to thank strangers for congratulations and condolences I appreciated, but couldn’t fully accept. Like a birthday gift you get as a kid that’s not the toy you asked for, I said thank you but wasn’t fully grateful. A bratty perspective you just can’t shake free from.

I hadn’t gotten it done.

And yet the messages still kept appearing.

Somehow, to my surprise, the act of not qualifying appeared to be more inspiring than if I was 2 seconds better.

“I don’t know how you’re handling this, I’m afraid I’d be shattered,” a woman confessed to me.

Speechless, I continued to try and make sense of it myself.

Three days after

“I still don’t know if I understand it.” I messaged a friend.

“I don’t mean to be naive, I appreciate the support, but why is coming up short more inspiring than if I’d qualified? What about all the guys who beat me and are going to Atlanta? Wouldn’t it be better if I was like them, if I was faster?” I questioned.

“I think it’s cause it was always going to be a razor-thin margin.” He replied.

“It was going to take everything you had and wasn’t a guarantee. And you were still willing to give everything to it. That’s what’s inspiring to people.”

Another deep breath and difficult swallow, I thanked him.

Clearly missing by so little reinforced to others what’d been painfully apparent to me: this dream was way out of my control. The truth that the marathon can’t be tamed was so obvious that it had strung a thread of urgency and meaning through each day of the previous two years inside this dream. I had understood that if I wanted to achieve this outcome I needed to do more, try harder, and focus more intently than ever before.

And even after all that, I'd failed.

Again.

Shaking my head slowly, I continued clenching my fist in frustration, as tears welled in the edges of my eyes, days removed from the finish line moment I couldn’t seem to get past.

Four days later

“I have something I need to tell you.” I offered Julia sheepishly.

“What’s that?” she asked, bracing herself slightly.

“I’m thinking of going to Houston.”

“Oh, yeah…I mean, I kind of assumed. I thought you were gonna say something bad.” She sighed in relief.

Apparently, the task at hand was obvious to others.

“I guess I’m just nervous. More than ever before.” I confessed.

It felt silly to care so much, to get so worked up, about something of little consequence. After all, in a world of increasing complexity, that’s heating up rapidly, tearing itself apart politically, and losing its way economically, what does qualifying for a footrace matter?

What had become most clear in attempting to qualify was that the point of all this was to maximize. To feel something. To turn the volume on life all the way up and stare straight at the scariest, most exciting challenge you could find without looking away.

But many of my peers from my running past had stopped. Most hadn’t continued to select higher goals that scared and inspired their heart. I’d watched too many friends drift back to earth because they let the sails of their ambition fall slack. I understood that this window of my body’s ability wouldn’t remain open indefinitely.

No, the promise of faster tomorrows evaporates eventually without your approval. Having seen it close on others slowly at first, and then all at once, it was now painfully clear to me what the dream at hand demanded.

I had to run.

One day before the Houston Marathon

There was no way to know how the next day would go. The weeks after CIM I had felt sapped, dejected, and sad. Emotionally somersaulting each day between disbelief at my near miss and hope for a final chance.

With just 12 hours remaining before the final attempt at this wild dream something dawned on me: I felt incredible.

Having forced my body to begin moving through the motions of training before my mind could make sense of it I’d managed to complete several workouts that actually gave me hope.

“You know, you did run your personal best, feeling your best, just a few weeks ago.” I reminded myself cautiously.

“What if, instead of thinking of yourself as an empty vessel, a spent rocket, you’re actually a recovered racer with more ability than ever before?”

“What if tomorrow could actually go great?!” I shocked myself with the most obvious question.

I was ready to race again.

The 3rd attempt — The 2020 Houston Marathon

A morning of déjà vu preparations. And we were off.

Today was crisp and fast.

“Is this the 2:19 pack?” A man inquired as he caught us from behind.

“2:18 pack.” A deadpanned.

“Every second counts.”

The men surrounding me were prepared. It was deadline day and we were on a mission.

And I was running free. Having familiarized myself with failure, my stride and spirit felt light, as if unburdened by the cloud of disappointment that had followed me the past month. Sprinting at pace through streets lined with well-wishers, I was where I belonged, thankful, and able for one last attempt.

The only issue was I was a bit stuck.

Off the back of a faster pack, and ahead of another, I was isolated without clear cover from the wind. Which would become an issue. Miles passed with ease and the spirit of the day began to carry me through. To feel this good, again, so soon, was a distance runner’s dream.

But then we turned toward the gusts.

Still striding with strength, the blowback was subtle at first, then stronger, then stronger still. Glancing at my watch, the pace was precarious; not yet a disaster, but not quite fast enough to qualify.

A mile split: too slow.

Another: even slower.

Panicked, I was too far from the finish to go any faster.

“Shit.” A cloud of dread was forming over me even as the crisp sun rose.

I was fucked.

Slightly past half-way, the pace was too slow and I had too far to go alone. Being blown about by the increasing wind, I still felt incredibly able, I just wasn’t moving quite fast enough.

Frantic, my mind scanned through options of what to do next.

“Do I drop out?” I puzzled. I only came here for one reason, what’s the point in even finishing any slower?

“Don’t be absurd.” I scolded. But the thought of covering the next dozen miles slower than qualifying pace was too much for my mind to process.

“What an imposter!” I screamed at myself inside. “All those people, all those well wishes, and you’re pissing it away again! You idiot.” Wallowing, I continued to run without a plan.

But then I heard it.

The stampede was coming.

The steady pack of OTQ paced hopefuls was about to roll me up. I knew how this goes. I’d watched it many times as a fan. The struggling runner tries to hang on, gives it a shot, fights briefly, before the pack eventually, relentlessly, rolls on without him.

“You’ve got one fucking chance to reattach and then it’s over.” Like a surfer about to drop in on the last big wave of his dream set, I breathed deeply and slipped in with the others.

Still processing waves of anger, disappointment, and sorrow for my race gone wrong, I was managing to hang on.

Fighting into the wind, we weren’t running quite fast enough, but it didn’t matter anymore. Having tried and failed to dictate the pace myself, I was now resigned to just hang on. My fate, the outcome of this dream, was in their hands. I saw the broken edge of a Texas sidewalk. Then the thick crimson stripe on the singlet of the man in front of me. Anything to distract my mind. There was no time left to think. Just run.

“Do these men believe more than me?” I wondered. Are they more talented, better prepared, or just mentally more willing to buy into the yet unfulfilled dream of being a Qualifier? Filled with doubt, I knew I was overthinking it, yet I couldn’t stop.

“Shut up and run!” I screamed inside. But this was me. For good, bad, and complicated, I was 23 miles deep into my third OTQ attempt, and I was…still on pace! I had nearly given up. Then fought an hour’s worth of mental battles. And yet remarkably, I still had a chance. But then came the wind again.

As the course turned, we were exposed once more, and surging once, twice, a third time confirmed that I could no longer keep up with the pack. I would have to fight these final gusts on my own.

Having spent two years fighting to cross the threshold of this marathon dream, the window closed in sixteen minutes.

No longer looking at my watch, I pushed harder.

Having burned through the inspirational power of all the well wishes I brought to Texas, I was down to one final figure, the person who always expects excellence of effort: my Dad.

Weeks before when I doubted whether I should come to Houston I had sensed his hesitation. I saw in his eye the perspective of an elder who understands the significance of a title. He would always love me regardless, but in these minutes, I had the chance to define myself for a lifetime.

I’d always run harder for him.

Kicking, surging, I was absolutely flying. Though likely slower than the Olympic Trials Committee demands, I was closing a marathon faster than I’d ever thought possible.

Rounding into the finishing straight, the scorching of my marathon legs was overcome by an ache inside my chest as I watched the lights dim and the curtain close on this amazing dream.

2:19:23

Waking up

Opening my eyes to a day outside the dream of the 2020 Olympic Trials felt like an organ had been ripped out of my chest.

Its absence was eerie.

A sound of silence lingered as the pressure of my purpose escaped and I decompressed into the feeling of daily life without direction.

I felt lonely and exposed.

The force that had propelled my running and absorbed my life for two years, was now gone. No matter where I was the past 25 months it had always been on my mind. Whether running a mile, hosting a meeting, or drinking a beer, I was aware of how that action fit in the scheme of my preparation towards the goal.

It had offered clarity, momentum, and meaning to each day.

“I’m sorry.” I texted Patrick.

Fully aware that remorse was unnecessary. That regret was implied. That hurling yourself against the castle walls of the qualifier three times only to come tumbling back down meant you tried entirely. But if you unraveled the dream completely, if you rolled it out fully, from a marathon goal, to a hope for running distinction, to a desire to be physically able, what you get to eventually is the simple vision of racing the best marathon of your life side-by-side with your friend.

We had an unspoken promise that we’d be there for one another at the Trials. Having given so much to me, my driving force during each attempt had been to be there for him on our sport’s greatest stage.

But it wasn’t a promise I was able to keep.

Although the ability to fly at such a speed is intoxicating, at some point I’d discovered that the quest to become a Qualifier stopped being only about running. Somewhere between rising for thousands of miles over years, and sharing the meaning of those moments with others along the way, I had propped open the door on our collective desire to dream that most often sits closed.

I had wanted to be good enough. For myself and everyone that had invested their emotions in me. Because amid life’s ambiguous layers of meaning, I had spent these years longing for the crisp, clear, irrefutable stamp that I’d done something.

“My heart beat for you today. I guess the world still needs heartbreak.” A friend wrote to me. His message illuminating the meaning that had emerged from this endeavor. Our dream had rested on my shoulders. Stood on my legs. Only my two feet could achieve the outcome that had captivated our imagination.

It had never stopped being about being better. No silver lining, secondary meaning, or soft landing could ease the pain of this failure. Because the purpose was to feel, even when it hurts.

Maybe especially when it hurts.

The Olympic Trials

As the start of the race I wasn’t running approached, my body began rattling with phantom nerves. Unsure of what was happening, I realized my mind was ringing an alarm that I had set long ago and forgotten to switch off.

The moment I’d dreamt of every day for years was about to occur, but I was standing inside sipping a cup of coffee. I couldn’t converse casually because I hadn’t prepared to be there as a fan.

As packs of our country’s best runners circled the city I felt an intense need to experience the race alone. To connect directly with the racers I so wished I could call peers.

Finding a spot on a bridge one-kilometer from the finish I screamed until my lungs were coarse, and then I screamed some more. I implored the men and women to embrace this moment, to not look away at the horrible beauty of the thousand meters remaining.

It appeared terribly painful for them all, regardless of their place. The top few sprinted by in fear of getting caught for their podium position. The next few surged past gripped by the horror of seeing their Olympic spot slip away. Some were charging, accomplishing heroic runs in their nation’s best marathon. But for many, I sensed in their eyes the ache of witnessing their longtime dream printed into reality. Watching as the goal that had motivated them for years faded from the glimmer of imagination to the muted tones of reality. Their salt-stained faces passed by in shock.

This was the dream. This was the moment we all longed for, taking place over a hilly, cold, windswept course. In all of its glory, agony, and prestige.

This was ugly.

It was wonderful and painful to watch. This course, under these conditions, had left the best marathoners in America exposed. Which was always the point: to find a test that would striate even our elite.

Such is the beauty of the marathon — making the most of themselves, together, there was nowhere for them to hide, not a moment to hold back.

Not racing there was a failure for me, sure, but in some ways, the entire event was about failure. The commitment of this whole endeavor was simple: to push until you lose control.

To reach that line.

Mine was right on the precipice of qualifying. For others, it was earning the “Qualifier” distinction only to be dropped off the back of the pack. And the pros, the very best who didn’t earn a podium spot, they had their faces pushed right up against the glass outside Olympic distinction. Cruelly forced to watch their competitors showered with accolades.

But embracing failure is the essence of our sport.

The foundation of this dream was simple: the ability to run fast at length. But as it expanded I was surrounded by a community aiming to endure until we were unable. Dreaming this grandly meant becoming so acquainted with our limits, so accustomed to living past our perceived abilities, that we took our mortality down off its safe perch on the mantelpiece of our mind and tossed it about, playing daily games with our humanity.

It meant feeling so invested in a pursuit that despite all other responsibilities and obligations we rose each day aware of what it would require and closed our eyes each night dreaming of how success would feel.

And in the end, once we each reached our inevitable edge, we were guaranteed two things: the heartache that we couldn’t go further, and the satisfaction that we spent each day along the way having never felt so alive.

More photos and stories, find me on Instagram

My weekly writing about running, The Positive Split, you can subscribe here

Other running stories can be found on peterbromka.com